About This Case Study

Little Tokyo is one of only three surviving Japantowns in the United States, currently navigating a unique tension between cultural preservation and the rapid expansion of the Downtown core. This work originated from a Master’s Economic Development Studio, where our team was tasked with drafting a comprehensive plan for the district’s future. While my colleagues focused on urban design and connectivity, I led the development of the housing strategy. The objective was to identify how development pressures from the new Metro Regional Connector could be managed, not just to build units, but to secure the community's longevity. What follows is an exploration of that balance.

Historical & Current Context

Little Tokyo’s built environment is defined by a cycle of settlement, displacement, and redevelopment. Established in the late 1800s, the district grew into the largest Japanese American enclave in the U.S. by the 1930s, housing 35,000 residents in a dense network of boarding houses and tenements. This vibrancy was violently interrupted by World War II incarceration, during which the neighborhood transformed into "Bronzeville," temporarily housing up to 80,000 African American wartime workers in overcrowded conditions. Post-war urban renewal projects, including the construction of civic centers and the Parker Center, razed entire residential blocks, thereby shrinking the neighborhood's footprint and significantly reducing the housing stock.

Despite these reductions, the community stabilized through targeted institution-building and preservation. The late 20th century saw the rise of critical anchors like the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center and specific housing interventions like the 300-unit Little Tokyo Towers (1975) and Casa Heiwa, which provided essential affordable units for seniors and low-income families. Today, Little Tokyo remains one of only three surviving Japantowns in the U.S., though its residential profile has shifted. The current population of approximately 3,000–4,000 residents is a fragile mix of seniors in legacy subsidized housing, low-income renters, and newer residents in market-rate developments, with a median household income that trails the citywide average.

Currently, Little Tokyo sits at a critical pivot point between heritage preservation and speculative growth. Designated as a "Village" place type in the DTLA 2040 plan, the neighborhood is facing intense pressure from the new Metro Regional Connector and its proximity to the Arts District. While these infrastructure upgrades increase accessibility, they also threaten the naturally occurring affordable housing that anchors the neighborhood’s cultural identity. Understanding this tension between a legacy of displacement and the immediate threat of gentrification is the baseline for our housing strategies, which aim to protect vulnerable residents while accommodating sustainable growth.

Housing Demographics Overview

Note: Data reflects census tracts partially overlapping the eastern edge of Skid Row. Figures should be interpreted as directional indicators for the Little Tokyo core.

Demographic Profile: A Renter-Driven Neighborhood

Little Tokyo is defined by high mobility and a dominance of renter households. The neighborhood is 91% renter-occupied, significantly higher than the city average. It is a transitional space for many, with 59.5% of residents having moved in since 2018, reflecting the transient nature of a central urban district.

Household composition is overwhelmingly small. Singles and couples make up nearly 90% of the renter population (55.6% one-person; 33.0% two-person), while family-sized households (4+ persons) comprise only 5.1%. This indicates a community primarily serving young professionals, students, and seniors, with a shrinking footprint for larger families.

The Affordability Gap & Housing Stock

The neighborhood’s housing stock is bimodal: it is characterized by a "dumbbell" distribution of age, featuring a significant cluster of pre-1940 legacy buildings (19.2%) and a modern wave of post-2010 developments (26.8%), with very little produced in the decades between.

Despite the influx of new supply, affordability remains the critical pressure point:

- Cost Burden: 54% of renter households pay more than 30% of their income on rent.

- The Income Disconnect: The burden is most acute at the bottom. 70% of cost-burdened renters earn less than 35% AMI, signaling a deep need for Very Low and Extremely Low Income units.

- Rising Rents: While 1-bedroom rents rose marginally (+4.9%), 2-bedroom rents spiked by 15.9% (2020–2023), placing disproportionate pressure on the few families remaining in the district and roommates sharing costs.

Current Assets: The district relies on key legacy affordable projects like Casa Heiwa, Little Tokyo Towers, and the San Pedro Firm Building. The pipeline includes the Go For Broke Plaza (248 units, 30–80% AMI), representing a critical opportunity to expand this inventory.

Defining the Need: Strategic Implications

Based on the demographic rift between high market rents and low-income burdens, our housing strategy focuses on four clear needs:

- Prioritize Deep Affordability: The data is clear: workforce housing (80% AMI) is not enough. With the majority of burdened renters earning less than 35% AMI, new interventions must target Deeply Low Income (less than 30–40% AMI) households to prevent displacement.

- Preserve Legacy Stock: Roughly 20% of the housing stock is pre-1940. These older buildings often function as naturally cccurring affordable housing. Rehabilitating them is the most efficient way to maintain current affordability levels and cultural identity.

- Right-Size the Unit Mix: While the market produces studios for singles, the sharp rise in 2-bedroom rents suggests a shortage of family-appropriate inventory. Strategies must incentivize efficient 2+ bedroom units to retain families and multigenerational households.

Strategic Action Overview

To address emerging housing needs in Little Tokyo, we propose four strategic actions to preserve existing units and develop new housing for the neighborhood’s increasingly diverse population.

Preserve and Rehabilitate Eligible Aging Buildings

Promote the Development of Family-Friendly Properties

Prioritize Development of Mixed-Income Housing

Enable Office to Residential Conversion

Preserving and Rehabilitation of Aging Properties

Little Tokyo’s history dates back to the early 1900s, when Japanese immigrants first established businesses along First Street. While new developments and taller buildings now overshadow some of the original façades, the district remains historic: approximately 40% of Little Tokyo’s housing stock predates the 1980s, and roughly half of those homes were built before the 1940s. These properties form the neighborhood’s backbone, anchoring its cultural character and serving as naturally occurring affordable housing. As demand increases, however, many of these buildings face pressure to convert to market-rate units or undergo redevelopment, threatening both local affordability and historic identity. Consequently, our housing plan aims to preserve and rehabilitate this legacy stock, extending its useful life, through a targeted set of strategies.

Creating a Revolving Line of Credit for Neighborhood Non-Profits

One challenge in preservation is the need to respond quickly when acquisition opportunities arise on the market. Assembling capital on short notice is difficult. Establishing a low-cost line of credit for rapid site control, followed by arranging long-term financing, allows neighborhood stewards to outcompete outside investors.

A successful model is the Urban Land Conservancy’s (ULC) Metro Denver Impact Fund (MDIF), a $75 million revolving loan fund supporting affordable housing, schools, and other community assets. The MDIF is capitalized through a partnership with FirstBank, which provides a $37.5 million, 10-year revolving line of credit, matched by $37.5 million in soft-debt investments from nonprofits, foundations, and public agencies. The fund offers low-cost, interest-only capital with a streamlined approval process, enabling ULC to move swiftly on preservation and development deals. In most cases, ULC retains long-term land ownership via a 99-year ground lease. As of 2023, the MDIF has financed about 40% of ULC’s portfolio, totaling $81 million.

The Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) is well-positioned to adopt this approach, as its reputation and service footprint across Los Angeles could attract broader capital from foundations and CDFIs. The organization could deploy a similar fund to acquire and rehabilitate aging buildings for affordability preservation and to secure infill sites during the predevelopment phase.

Raising a Joint-Equity Rehabilitation Fund

There are aging properties that may not be ready for full redevelopment but could benefit from renovations that extend their useful life. An emerging way to finance these improvements without adding owner debt is a joint-equity rehabilitation fund. Under this model, equity partners invest the capital needed to upgrade the building. Those improvements increase the property’s value and net operating income, extending the building’s lifespan and improving cash flow. In return, investors participate in appreciation and receive a share of the increased rental revenue.

In Little Tokyo, simply renovating naturally occurring affordable housing and raising rents to market is contentious, given the neighborhood’s need for affordability. We propose that neighborhood organizations and existing vehicles, such as the Little Tokyo Community Impact Fund, partner with the local government and philanthropic funders to create a blended fund. Grants and donations from partners such as the California Community Endowment and California Community Foundation would be used to leverage credit-enhanced revenue bonds (functioning as quasi-equity in the capital stack). In exchange for this support, owners would record covenants that convert a portion of the units to permanently affordable housing. This approach preserves and rehabilitates aging stock while creating lasting affordability with limited owner liability.

Beyond adding deed-restricted rentals, the same program could support Tenancy-in-Common or co-op conversions, offering attainable ownership where new-build condos are out of reach. Rather than continuing to rent, households could build equity in right-sized, older units that are often better priced for young families. These transitions could be financed through the joint-equity rehab fund and a revolving line of credit targeted to moderate-income buyers.

Promoting Family-Friendly Apartment Development

Little Tokyo has a distinctive demographic mix. On one side is an aging senior population deeply rooted in the neighborhood; on the other is a growing cohort of young professionals whose housing needs evolve quickly. Today’s unit mix and amenities often are not conducive to starting or raising a family, so many residents move on when their needs change. Our goal is to make Little Tokyo more family-friendly by adding larger units and in-building amenities that encourage couples and young families to stay and grow within the community.

Incentivizing Two and Three-Bedroom Units + Family-Friendly Amenities

Family-oriented units and amenities can be expensive to implement and maintain. They are riskier, as developers need to prove the young-family market, and larger units typically rent for less on a per-square-foot basis. To incentivize developers to include two- and three-bedroom units and family-oriented amenities, we recommend offering density and intensity bonuses, as well as funding opportunities for developer participation.

Under the Citywide Housing Incentives Program (CHIP), we propose introducing local criteria for the Little Tokyo neighborhood that allow developers to build more units on their site, increasing the allowed density and intensity, thus making the inclusion of family-sized units profitable. Additionally, we recommend introducing the opportunity for developers to include indoor amenities that count toward open-space requirements, such as on-site childcare, indoor playgrounds, or family-friendly fitness centers.

We also recommend exploring funding opportunities for developers who include family-oriented units and amenities. For example, we could create a NOFA under United to Los Angeles (ULA) that provides funding for the development of family-oriented properties. Moreover, we could introduce criteria in Prop A, a recent sales tax fund, to incentivize this type of development.

Building Mixed-Income Properties

As Little Tokyo evolves into a mixed-income community, it requires housing solutions that serve the entire economic spectrum. To sustain this diversity, we must incentivize a balanced housing mix that includes affordable, workforce, and market-rate units. This comprehensive approach preserves the neighborhood's social fabric, ensuring it remains accessible to a broad demographic, from seniors on fixed incomes and local service workers to caregivers and young professionals.

Leveraging Publicly-Owned Land to Subsidize Mixed-Income Properties

The neighborhood features several publicly owned vacant parcels that are ripe for residential development. We propose utilizing these assets to support developers of Low-Income Housing Tax Credit properties. By offering long-term ground leases at below-market rates, the city and county can significantly reduce development costs, helping these projects achieve financial feasibility. In exchange for this land subsidy, the City will enforce Land Use Restriction Agreements to guarantee that a portion of the units remain permanently affordable.

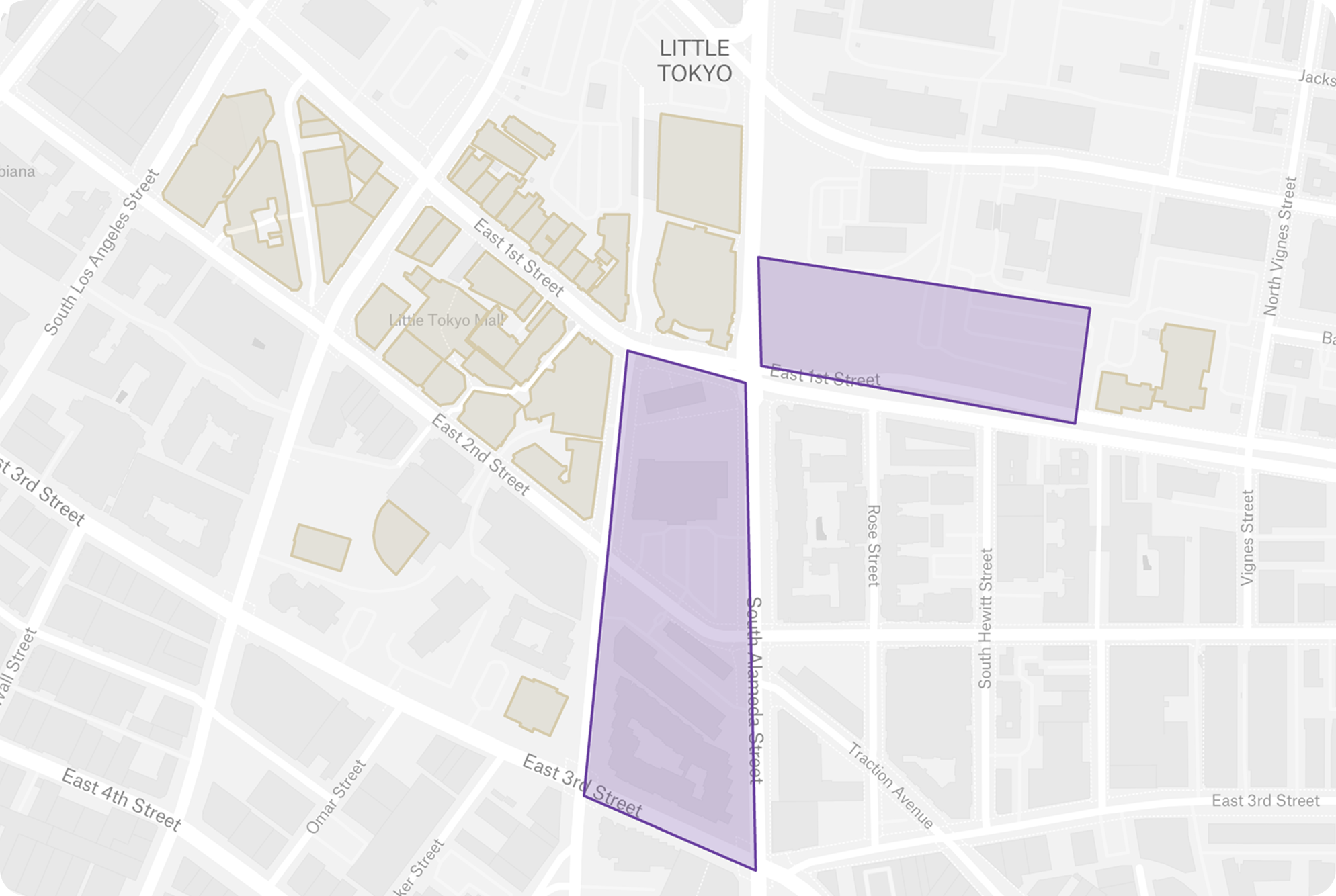

The purple area represents underutilized blocks and parcels.

Adaptive Reuse of Office Buildings

The post-pandemic shift to hybrid and remote work has left Little Tokyo with several underutilized and largely vacant office buildings. This trend presents a clear opportunity to convert these commercial properties into much-needed residential housing. The primary obstacle to these conversions is not a lack of interest, but the high cost, which often makes them financially infeasible.

Currently, the primary tool for encouraging these projects is the Citywide Adaptive Reuse Ordinance (ARO). This ordinance allows buildings older than 15 years to have by-right access to a suite of powerful incentives. These include exemptions from certain density limits and parking requirements, a streamlined planning review process, nonconforming protections for existing structures, and flexibility in minimum unit sizes. The ARO is designed to enhance a project's financial viability by eliminating key regulatory barriers that would otherwise incur prohibitive costs and delays.

Tax Abatements for Adaptive Reuse Projects in Little Tokyo

Despite available zoning relief, a structural financial gap remains for many conversion projects in Los Angeles. To make these complex renovations viable, we recommend implementing a targeted property tax abatement program for the Downtown area. This incentive would serve as a catalyst, transforming vacant commercial assets into productive residential communities.

Washington, D.C.’s "Housing in Downtown" program offers a compelling precedent, providing a 20-year tax abatement in exchange for a 15% affordability set-aside. We propose adapting this model for Los Angeles by amending the current ARO, which would involve implementing a 10- to 20-year abatement on the tax increment generated by the rehabilitation (the increase in value resulting from the renovation). Alternatively, the program could specifically abate the City’s portion of the property tax. In exchange for this fiscal relief, developers would be required to restrict 10–20% of the units as affordable housing for the duration of the abatement period.

Two potential office to residential conversions in our study area.

Conclusion

Housing does not exist in a vacuum; it is the economic engine that sustains local activity. This strategy was designed to operate in tandem with my team’s public realm and business proposals, ensuring a stabilized resident base, specifically seniors and growing families, remains to support Little Tokyo’s cultural institutions. The resulting framework offers a blueprint for how the neighborhood can absorb intense investment from the Regional Connector while remaining a vibrant, multi-generational home.